The war in Afghanistan has now entered its third American

presidency, a bi-partisan commitment to … to … to what? U.S. troops – uniformed and not -- are on the

ground and/or dropping bombs in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, The Sudan, and now

apparently Niger, and who knows where all else. Did I point out none of these countries have been mentioned in a

declaration of war by the Congress, the only body authorized by the

constitution to make such a declaration?

Yet … soldiers die in the thousands and civilians die in the tens of

thousands.

At home, people question whether a call

to console gets made, yet nobody ever seems to question the call to arms. Isn’t it time for a rethinking of American foreign policy?

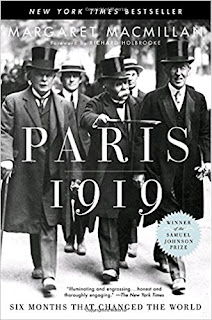

One could begin with a history book or two, though one must

wonder if the current, temporary occupant of the White House has ever read a

history book. His ignorance of all things involving governing is a problem, but in all

fairness American foreign policy was a mess even before he was foolishly

entrusted with it.

The books don’t even have to be “history,” they could be

fiction, and The Ugly American by William Lederer and Eugene Burdick would make

a good starting point. If a president

doesn’t have sufficient attention span for a book, he could perhaps watch the

movie.

Published in 1958, The Ugly American is set in Southeast

Asia as the French are being driven out of "French" Indo-China, which would soon

become the United States’ nightmare in Vietnam.

The country the book is about is Sarkhan, fictional, yet familiar. In the book, Americans have gone to Vietnam

to try and understand how the Communists are so successfully dislodging the

French in the hope of preventing that from repeating itself in Sarkhan. In the movie, the action begins

in Sarkhan, with the domino theory the overriding policy concern.

The American foreign service (State Department) is savaged

in the book as incompetent, practitioners of imperialism at its worst, and

arrogance at its most blatant. The

protagonist in the book, Homer, an American farmer, serves as a role model for what the authors

believe America’s role in the world should be. Today we would recognize Homer’s

strategy as the Peace Corps, created by Executive Order by President Kennedy

just a few years after the book was published. The movie adaptation of The Ugly

American was released six months before the Kennedy assassination.

The timing of the book is important – the year after its

publication, the revolution in Cuba succeeded in deposing the puppet government

and founding the first communist government in the western hemisphere (Cuba is

not mentioned in the 1958 book but is mentioned as an example of policy failure in the 1963 movie). At the time, and with puppet governments and colonial “protectorates”

all over the globe, the West was fearing the loss of “its” possessions, and the

rise of Soviet and Chinese dominance. That sphere of influence debate

continues today.

As always, my preference is that people read the book,

however I will qualify that this time by advising that the movie, starring

Marlon Brando as the U.S. Ambassador to Sarkhan, is also important.

In the final scene, with Sarkhan in revolt,

the Ambassador makes a press statement. A few sentences into his statement at

the embassy, the movie cuts away to an American living room where his press

conference is being viewed on a black and white television set. The viewer listens for a few brief moments

then, just as the Ambassador is beginning to acknowledge U.S. foreign policy errors, picks up and glances at a TV Guide, then switches channels. “The End” displays

on the television screen.

Recommendation: Should be required reading for candidates for President.